Tsuru, Daisaku

1. Self-introduction

I am engaged in anthropological research and do fieldwork on the Baka pygmies (who call themselves “Baka”) in southeastern Cameroon, Africa. The Baka, as with the Mbuti pygmies (in the former Zaire) being researched by Mitsuo Ichikawa (in the ASAFAS), dwell in forests and have, for the most part, a hunter-gatherer lifestyle. Among the different pygmy groups, the Aka and Efe are the most recognized, but all have similar lifestyle practices and are believed to form a single cultural group.

2. Research on Baka spirit rituals

My research focuses on the rituals and religion of the Baka people. Not much research has been carried out on the topic of religion among pygmies, leaving plenty of room for inquiry. Among the different pygmy groups, there is belief in supernatural “spirits of the forest” known by the Baka people as “me.” Rituals for the spirits are often performed as part of life in Baka villages (about 50 people in each community). The men of the village form groups to perform the rituals, and using clothing that conceals the identities of the performers, convincingly stage the presence and actions of the spirits, mostly for women and children to enjoy.

These rituals work to ease social tensions among the community and are important in strengthening group unity. I call these “spirit rituals,” and made them the focus of my research. I ask the basic questions of why the Baka people stand by spirit rituals and continue to perform them. That is, what is it that makes the spirit rituals appealing and amusing for the Baka people?

The huts that house each nuclear family face each other around an open space, which is often an area where the forest has been cleared. To the left in the photo can be seen the entrance to a njanga, which is a spirit dwelling. This is similar to Shinto shrines, and people are usually not allowed to enter it.

A mongulu under construction. A special hut made of foliage called a “mongulu.” It is the task of women to make these.

3. Ritual performances of the spirits and variations thereof

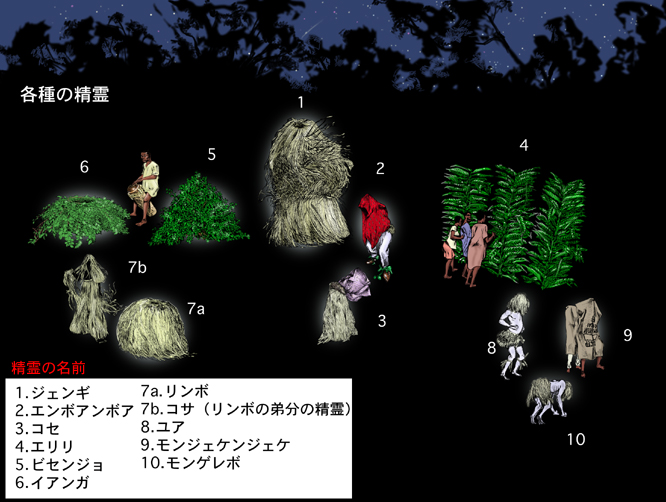

Intriguingly, the spirits are dressed in an abundant variety of ways.

Here are photographs of some of the Baka spirits.

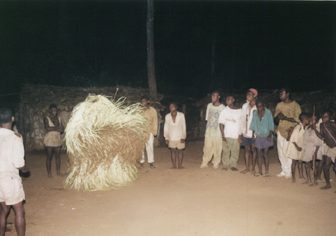

A Jengi dancing as the villagers sing. The Jengi is regarded dangerous, so women and children do not get close to it.

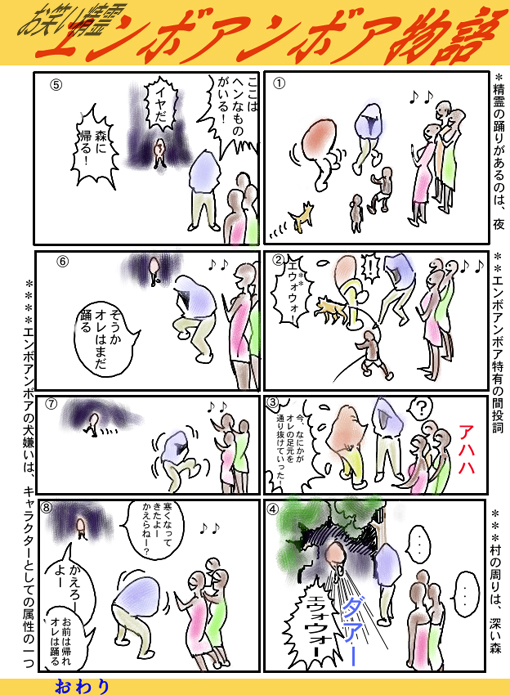

The Emboamboa is, if anything, a foolish spirit, and the children here are playing with it.

A grass skirt that makes sounds is attached to the hips of the Kose, and it is constantly being rhythmically shaken.

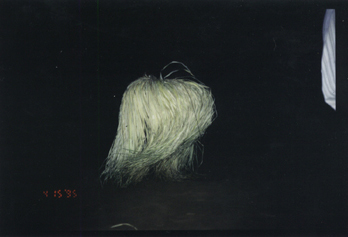

limbo is like the Jengi but smaller. Unlike the Jengi, the dancer inside the costume is on all fours.

4. Spirit characters

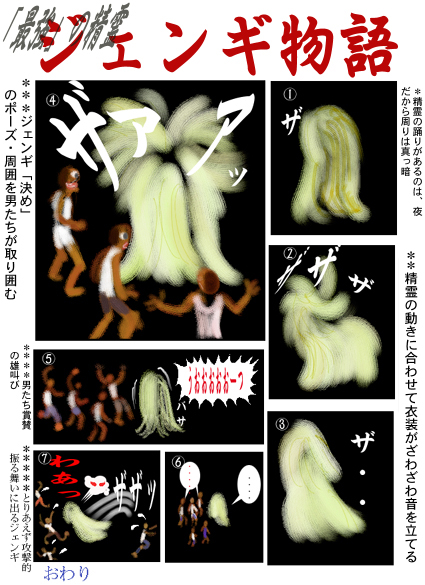

I have reproduced cartoons below of character representations of the Jengi and Emboamboa, typical spirits of the Baka people.

The character representation of the Jengi, considered the highest ranking of the spirits, aims to overpower and overwhelm the viewer. By contrast, the Emboamboa is a kind of clown, and the aim of it is to bring about amicable feelings. I have compiled my observations of the “personalities” of these spirits in the paper below.

Kameroon, Shuryosaishumin Baka no Seirei Pafomansu: Toku ni Seirei no kyarakuta Hyogen nitsuite no Kosatsu (The Spirit Performances of the Hunter-Gatherer Baka People of Cameroon: Focused Study of Spirit Character Representations)” in Dobutsu Kokogaku (Animal Archeology), No. 10, 1998, pp. 81-118.

5. Spirit performance and music

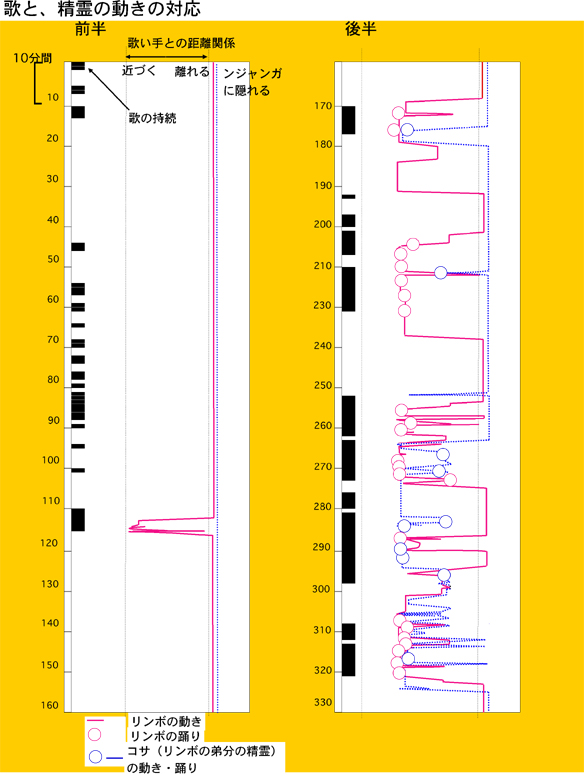

It is also believed that the spirits interact with humans through music. They mostly dance to the singing of the women while emerging from and retreating back into the bush behind the village, energetically moving into and away from it.

Village layout and spirit movements

The spirits have various improvised movements, and spectators are never bored. The women sing enthusiastically to make the spirits dance as they are stimulated by the variety of movements they perform. I am currently preparing my dissertation on the reciprocity between such dance and music in spirit rituals.

In this way, we can observe that the people’s enjoyment of spirit rituals is deepened through the multiple effects of such character representations and music.

6. Spirit ritual diversity and intra-cultural diversity

It is now considered necessary to perform a comparative study of spirit rituals with groups other than the Baka people, such as with the Aka and Mbuti peoples. However, there are many different types of spirits even among the Baka people, which vary even among the Baka villages. Before making inter-cultural comparisons, we need to properly understand the structure of intra-cultural diversity.

I have written two papers from this perspective, based on my study of the social process that gives rise to the diversity of the Baka spirits.

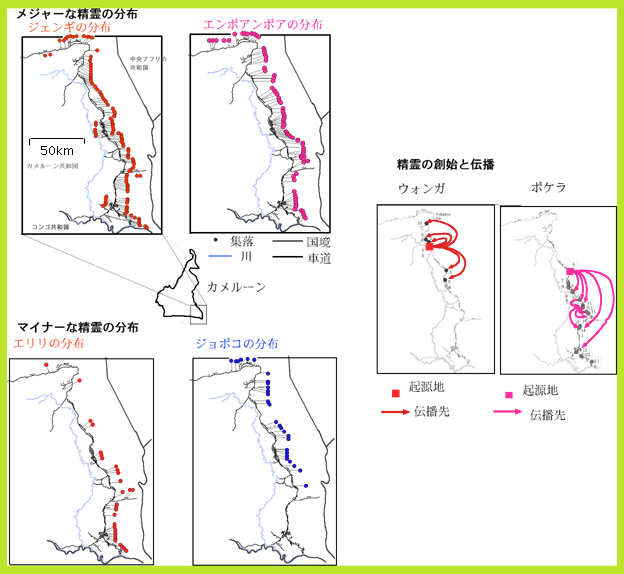

By studying spirit rituals in a wide-reaching survey of 227 villages along a logging road in the survey area, I identified 53 types of spirits, and I came to understand variations in the way they are distributed.

Variations in spirit distribution.

While spirits such as the Jengi and Emboamboa introduced above, for example, are common and could be found in more than a hundred of the villages, many of the other spirits were found in only 10 to 20 villages at most, and in many cases, only in a single village. The Baka people have a particular belief that spirits belong to specific individuals, which has a lot to do with the types of spirits that exist and how they are distributed.

Firstly, there is diversification due to many individual Baka people creating new spirits. Many spirits, however, are bought and sold among them, and in this process of exchange, some are favored and propagated far and wide, whereas others are not as popular and disappear. In other words, some spirits “die out.”

When talking about Baka spirits, there is a tendency to focus only on more conspicuous examples such as the Jengi, but to understand the basis for their foundation, there is a need to also consider the countless variety of spirits in the background. There are snatches of reports of the same fluid properties existing even regarding the spirit rituals of other groups such as the Aka and Mbuti, so this is a factor that cannot be ignored in making inter-cultural comparisons.

7. The Future: Is this a dynamic system for the generation of culture?

In considering Baka spirit rituals overall, we can depict a dynamic system that while continuing to produce what is standard, which includes the Jengi, is constantly changing. For the time being, this perspective regards the various types of spirits as being in competition with each other. Thus, in ritual performances, for example, the mechanisms used by spirits to entertain people can perhaps be seen as tools for them to “survive” in people’s hearts. Well-known spirits such as the Jengi can be regarded as ones that, due to some reason or another, enjoy great popularity and are “successful.” However, we cannot know whether a new spirit that the Baka people find more appealing will someday emerge and replace the Jengi. Conversely, perhaps one day (and I hope not), spirits themselves will become extinct, disappearing from people’s hearts due to a sudden environmental change of some sort (e.g. radical modernization or conflict).

Technically, this manner of thinking is similar to evolutionary ecology – that living things of different species make up an ecosystem as a whole as they relate with each other, sometimes competing. Furthermore, we can even say that although there are of course differences between the Baka and the Mbuti spirits, these are probably due to differences in the evolution of their respective ecologies. I may be too enthusiastic, but I sometimes even fantasize whether we can theorize about an “ecological history of culture (?)” based on materials about pygmy spirits.

To do this, there is the issue of a severe lack of research paying heed to the matter of intra-cultural diversity. This is because anthropological research generally tends to focus immediately on diversity between cultures. In the future, there will be a need for a perspective that avoids simple comparisons, and for the study of cultures all around the African continent (not limited to pygmy spirits) and an understanding of each as dynamic in nature.